Won’t somebody tell me . . . ?

Blind Willie Johnson, lead vocals and guitar

Willie B. Harris (BWJ’s wife), vocals

“Soul Of A Man,” Atlanta, 1930

Vodpod videos no longer available.

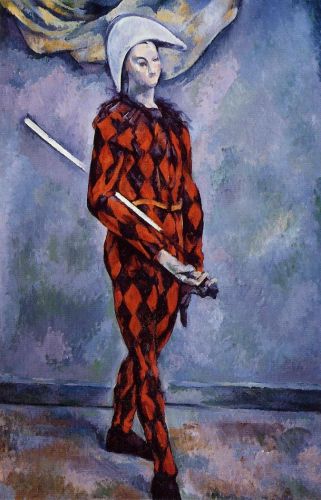

(The guy in the photo is Chris Thomas King, who portrayed Blind Willie Johnson in Wim Wenders’ The Soul of a Man, which aired on PBS as part of Martin Scorsese’s The Blues.)

More? Here. And here.

**********

lagniappe

Blind Willie Johnson, a gospel singer, preacher, and pioneer of the blues, understood the power of the honest question, and he perceived its flame in the Bible.

Johnson was born in poverty in 1897 and blinded at age 7, when his stepmother, in a fight with his father, threw lye in his face. He died in poverty in 1945, sleeping on a wet bed in the ruins of his house, which had burned down two weeks before. Thankfully, between 1927 and 1930, he recorded a number of his biblically based blues songs with Columbia Records. These have inspired countless rockers, from Led Zeppelin to Beck. In 1977 his “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground,” a hauntingly inarticulate meditation on the Crucifixion, was sent into deep space on the Voyager 1 as part of the Voyager Golden Record, a collection of music representing the sounds of Earth to any potentially interested extraterrestrials. The time capsule is scheduled to be within 1.6 light-years of two nearby suns in about 40,000 years. The closest thing to timeless any musical artist could possibly achieve. Mercy, how we do so often love to immortalize those despised and forgotten in life.

Johnson’s uniquely spiritual blues music is driven by the deepest questions, often finding voice through an encounter between biblical tradition and his own life experience, which was well acquainted with sorrow. The Bible peopled his imagination. It was his wellspring of imagery. It empowered him to call this world into question and to envision another. On at least one occasion, the powers that be recognized how potentially explosive such an inspired combination of biblical language and lived oppression could be. He was arrested in front of a New Orleans city building for inciting a riot simply by singing “If I Had My Way I’d Tear the Building Down,” a song about the biblical hero Samson, who tore down the house of the Philistine lords after they had gouged out his eyes. To the officer who arrested him, the ancient story suddenly sounded dangerously contemporary.

In his well-known song “Soul of a Man,” Johnson growls out the question he has pursued his whole life, knowing that no one can really help him find the answer: Just what is the “soul of a man”? Indeed, what is soul? It’s a question filled to overflowing with other questions. Am I more than my mind? More than my body? More than the sum of my parts? Do I have a soul? Does it live beyond this mortal coil? What am I? Who am I? Why am I here? Such profound questions are often asked, but too often are followed by erudite answers from someone who claims to know. Rarely by someone who honestly does not know. As none of us do.

Johnson recalls his lifelong soul search. He’s traveled far and wide, through cities and wildernesses. He’s heard answers from lawyers, doctors, and theologians. None have satisfied. In response to each of the answers he’s been given, he repeats his question with more forceful, gravelly urgency.

In his quest, he turns to the Bible:

“I read the Bible often, I tries to read it right

And far as I could understand, nothing but a burning light”

Called to preach since age 5, steeped in the African-American Baptist tradition, this blind sage of spiritual blues knew the Bible inside and out from memory. Yet it gave him no answer, only a more profound mystery: nothing but a burning light.

—Timothy Beal, “The Bible Is Dead; Long Live The Bible,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 4/17/11

*****

listening room: what’s playing

Tinariwen, The Radio Tisdas Sessions (World Village)

Tinariwen, Imidiwan: Companions (World Village)

Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star (Rawkus)

Various Artists, Life Is A Problem (Mississippi Records)

Various Artists, Oh Graveyard, You Can’t Hold Me Always (Mississippi Records)

Various Artists, Powerhouse Gospel on Independent Labels, 1946-1959 (JSP)

Arvo Part, Miserere (ECM)

WFMU-FM

—Give the Drummer Some (Doug Schulkind), 9 a.m.-noon (EST) (web stream only)

WKCR-FM (broadcasting from Columbia University)

—Eastern Standard Time (reggae), Saturday, 7:30 a.m.-noon (EST)

—Traditions in Swing (Phil Schaap), Saturday, 6-9 p.m. (EST)

—Duke Ellington birthday broadcast, 4/29/11

*****

art beat

What brings folks here? It’s not what you might think (if, that is, you were to give this any thought). When it comes to searches, what brings the most people here isn’t music; it’s paintings. “Captain Beefheart paintings,” “de Kooning excavation”: hundreds come here looking for them.