music clip of the day

Tag: Vincent van Gogh

2016

Saturday, March 26th

otherworldly

Iancu Dumitrescu (1944-), Infinity for bass clarinet and ensemble, Hyperion Ensemble (feat. Tim Hodgkinson, clarinets), live, Bucharest, 2009

#1

***

#2

I love watching this guy conduct.

**********

lagniappe

art beat: other day, Art Institute of Chicago

Vincent van Gogh, Parisian Novels, 1887 (Van Gogh’s Bedrooms, through May 10th)

2015

Sunday, March 15th

sounds of Chicago

Caravans (feat. Shirley Caesar, lead vocals), “God Don’t Need No Coward Soldier” (J. Herndon), live (TV show), early ’60s

**********

lagniappe

reading table

You can live three days without bread—without poetry never.

—Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867; quoted in Julian Bell, Van Gogh: A Power Seething)

2014

Tuesday, December 23rd

Here are two more takes on the song we heard Sunday (“Leaning on the Everlasting Arms”)—both from Hollywood.

Robert Mitchum with Lillian Gish, The Night of the Hunter, 1955

***

Van Johnson, et al., A Human Comedy, 1943

**********

lagniappe

art beat: more from Friday at the Art Institute of Chicago

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), A Peasant Woman Digging in Front of Her Cottage, c. 1885

2014

Sunday, December 21st

three takes

“Leaning on the Everlasting Arms” (A. Showalter, E. Hoffman)

Five Blind Boys of Mississippi, live (TV show)

***

Mahalia Jackson, live (TV show), 1961

***

Iris Dement, recording (Lifeline), 2010

**********

lagniappe

art beat: Friday at the Art Institute of Chicago

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), Self-Portrait, 1887

2014

Saturday, November 1st

voices I miss

Leroy Jenkins (1932-2007), violin, live (“Lush Life” [B. Strayhorn], “Keep on Trucking, Brother (A Message to Bruce)” [L. Jenkins], “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” [Trad.]), New York, 1977

**********

lagniappe

musical thoughts

A jazz musician playing alone is like a tightrope walker working without a net. Playing a music of rhythmic verve, he lacks a rhythm section. Playing a music of spirited interplay, he lacks the company of others. And when the musician’s instrument happens to be the violin, he’s working not only without a net but without a tightrope.

The violin lacks all the advantages of the one instrument with a long-standing tradition of solo jazz performance, the piano. Where a pianist can play more than one musical line at a time (accompanying herself with her left hand, for example, while “soloing” with her right), a violinist can’t. Where a pianist can readily play complex chords, a violinist is limited to four strings and beset by innumerable fingering problems. And the range of pitches available to a violinist is only about half that available to a pianist. When a jazz violinist steps onstage by himself, he either falls flat on his face or, defying the conventions of gravity, flies.

Last Friday at HotHouse, jazz violinist Leroy Jenkins not only flew but soared. A dignified man so diminutive that he makes a violin appear large, Jenkins focused the listener’s attention not on what was absent—other musicians, multiple lines, an expansive tonal range—but on what was present. His concert provided a response of sorts to the familiar Zen koan: What is the sound of one hand clapping?

Playing for a small but attentive audience, the longtime associate of the Chicago-based Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians—who hadn’t performed here for several years—displayed a powerful and original musical vocabulary. Just as a poem forces one to consider language word by word, a solo jazz performance forces one to consider music sound by sound. And that was how Jenkins constructed each of his pieces: sound by sound.

He began most of them with a simple melodic statement that sang. Then he would veer off into gradually accelerating repetitions of two-, three-, and four-note patterns. Unlike a horn player, he never had to stop for breath, so these patterns could go on and on. Out of them would emerge long, winding bursts of melody, like swallows taking flight through a swarm of bees. Then Jenkins would return to repeated patterns, steadily building the intensity until he reached a climax and suddenly stopped.

The narrative structure of many of his pieces was thus not unlike that of a sexual encounter. But the steadily mounting intensity was invariably coupled with precise articulation, lucid organization, and exquisite control. When near the end of his set Jenkins rocked back and forth like a man possessed, his seemingly unshakable control of his instrument only heightened the dramatic impact.

A master colorist, Jenkins called forth a seemingly limitless array of sounds, from singing to fluttering to stinging to rasping to wheezing. But what was ultimately even more impressive than the variety and virtuosity of his playing was its logic and coherence. And unlike some jazz musicians, whose solos can be neatly divided into segments “inside” or “outside” normal harmonic and tonal conventions, Jenkins’s playing was all of a piece.

Jenkins’s HotHouse set readily calls to mind Richard Goode’s magnificent recent performance at Pick-Staiger Concert Hall of five Beethoven piano sonatas. Neither musician spoke a word to the audience, but neither seemed remote. Both played so wholeheartedly that they virtually disappeared in the music. Both are virtuosos who put their virtuosity entirely at the service of the music, never exploiting it simply for effect. Both played music that often pitted a coming-apart-at-the-seams emotional intensity against an ultimately prevailing clarity and order. Perhaps one day, solo jazz concerts of the caliber of Jenkins’s will be met with the same degree of anticipation and excitement that performances of Beethoven piano sonatas by artists such as Goode typically receive today.

—Richard McLeese, “Flying Solo,” Chicago Reader, 10/27/1994

*****

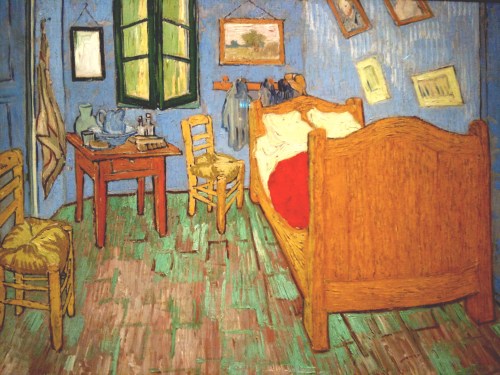

art beat: yesterday at the Art Institute of Chicago

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), The Bedroom, 1889

2014

Thursday, October 23rd

never enough

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), String Quartet No. 14 (Op. 131, C-sharp minor; 1826); Takács Quartet, live

**********

lagniappe

musical thoughts

Opus 131 . . . is routinely described as Beethoven’s greatest achievement, even as the greatest work ever written. Stravinsky called it ‘perfect, inevitable, inalterable.’ It is a cosmic stream of consciousness in seven sharply contrasted movements, its free-associating structure giving the impression, in the best performances, of a collective improvisation. At the same time, it is underpinned by a developmental logic that surpasses in obsessiveness anything that came before. The first four notes of the otherworldly fugue with which the piece begins undergo continual permutations, some obvious and some subtle to the point of being conspiratorial. Whereas the Fifth Symphony hammers at its four-note motto in ways that any child can perceive, Opus 131 requires a lifetime of contemplation. (Schubert asked to hear it a few days before he died.)

—Alex Ross, “Deus Ex Musica,” New Yorker, 10/20/14

*****

lagniappe

art beat: yesterday at the Art Institute of Chicago

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), The Poet’s Garden, 1888

2012

Saturday, 2/4/12

lighter than air, funkier than dirt

Otha Turner (1907-2003) and the Rising Star Fife and Drum Band (with guest Luther Dickinson, guitar), “My Babe,” live, Memphis, 1990s

**********

lagniappe

art beat: more from Wednesday’s stop at the Art Institute of Chicago

Vincent van Gogh, The Poet’s Garden (1888)

*****

musical thoughts

Last night, at the University of Chicago’s Mandel Hall, I heard what may be the finest encore I’ve ever heard. After devoting the second half of his concert to Beethoven’s mammoth Diabelli Variations, pianist Peter Serkin, following several trips offstage to rapturous applause, sat down and played, slowly, meditatively, the Aria from Bach’s Goldberg Variations. As the last note was fading, if someone had turned to me and said, with the kind of confidence one often encounters in Hyde Park, that the greatest achievements in the history of humanity can be heard at the piano, I couldn’t have done anything other than agree.